George William MacArthur Reynolds (1814–79) was one of, if not the, biggest-selling novelist of the Victorian era. Born in Kent, he was originally destined for a career in the navy, which was the path followed by his father. Upon his father’s death, however, Reynolds and his brother Edward took their inheritance and embarked for France. Upon arriving in Paris the Reynolds brothers appear to have ‘lived it up’ and they soon squandered their inheritance. After this, to support themselves, there are rumours that, like some of the rogues in Reynolds’s novels, they took to cheating unsuspecting players at cards. Then he turned to journalism to make ends meet while holding down a second job as a bookseller and publisher at the Librairie des Estrangers, or French, English, and American Library. It was with this company that Reynolds published his first novel titled The Youthful Imposter (1835).[1]

By 1837 Reynolds had returned to England and assumed the editorship of the Monthly Magazine, a magazine in which he published more novels in serial form such as Pickwick Abroad (1837–38), The Baroness (1838) and Alfred de Rosann (1838). Although Reynolds was an enthusiastic promoter of French literature, writing two volumes of literary criticism and translating some of Victor Hugo’s selected works,[2] Reynolds also had a fondness for Italian history and culture. One of his first short novels was titled ‘The Sculptor of Florence’, set in the famous Italian city during the seventeenth century.[3] He would go on to write other novels set in Italy such as his 1848–49 serial The Coral Island; or, The Hereditary Curse—the Italian connection is more obvious in the novel’s alternative American title: The Mysteries of the Court of Naples.

During the 1840s Reynolds became a Chartist activist and it was Reynolds who, in his capacity of newspaper editor, through a special feature in Reynolds’s Political Instructor first introduced the Italian patriot Giuseppe Mazzini to radicals in Britain.[4] It is Reynolds’s most famous ‘mysteries’ novel, The Mysteries of London, (published in weekly instalments between 1844 and 1848) to which we now turn to examine his portrayal of Italy.

Most of the scholarship on The Mysteries of London has focused upon the ‘First Series’ and its place in the development of the ‘mysteries’ genre.[5] Other scholars have focused upon Reynolds’s portrayal of a wide variety of issues affecting the urban poor such as organised crime.[6] The ‘Second Series’, contained in the third and fourth volume of Reynolds’s tale, remains almost entirely and unjustifiably neglected except for a commentary in Mary Shannon’s recent monograph titled Dickens, Reynolds, and Mayhew on Wellington Street (2015). Yet Reynolds’s Mysteries as a whole was popular and there is no evidence to suggest that only the ‘First Series’ was read by the Victorians and scholarship should reflect this. This article, I hope, goes some way to remedying this dearth of scholarship by examining both the ‘First’ and ‘Second’ series, which Reynolds himself viewed simply as one long novel alongside his long-running follow-up The Mysteries of the Court of London (1849–56), which is not actually set solely in London but contains scenes set in France, Italy, Australia, and India.[7]

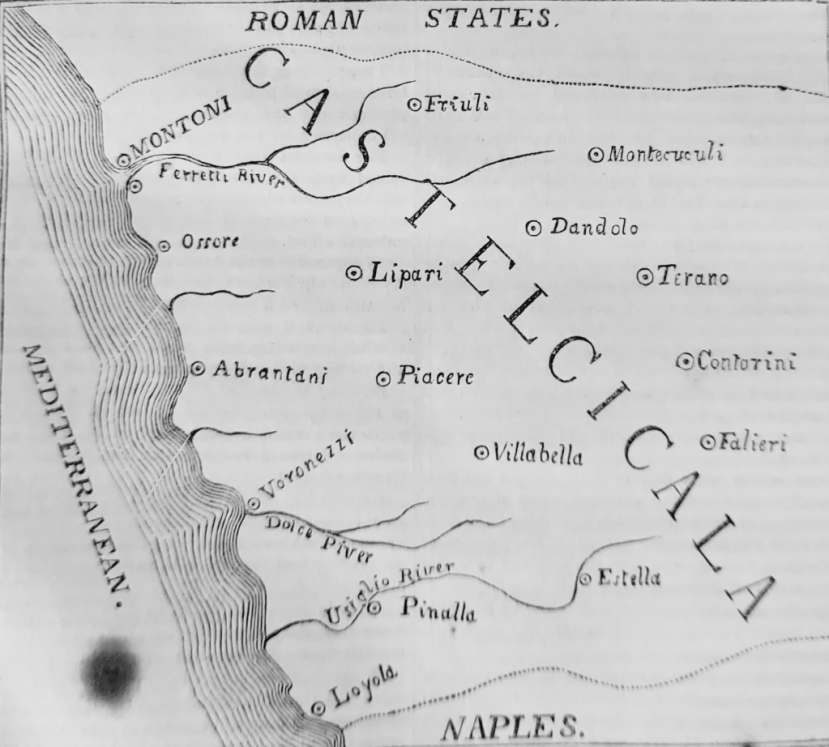

Italy is of course the focus here, and when Reynolds was writing Italy was not a single unified nation state but was instead a collection of small kingdoms and dukedoms.[8] English readers would have spoken of ‘Italy’ much in the same way that ‘the Balkans’ are spoken of today—as a region consisting of a collection of states rather than a single country. This political situation is reflected in Reynolds’s novel. In The Mysteries of London Italy, alongside Britain, is one of the primary settings. Readers are introduced to the fictional Italian state of Castelcicala, located just below the Papal States, which to begin suffers under the despotic rule of Grand Duke Angelo II. The hero of the novel, the virtuous Richard Markham, undertakes to reconquer Castelcicala with an army of rebel Castelcicalans for its former progressive ruler Grand Duke Alberto, who was exiled to London after attempting to give the Castelcicalans a democratic constitution (Markham has, after all, fallen in love with Alberto’s daughter Isabella and wants to prove his worthiness to marry her).

Markham’s military endeavours are successful and soon Grand Duke Alberto is restored to the throne, the Castelcicalans are given a constitution, and upon Alberto’s death Markham succeeds him as Grand Duke. As I show here, Reynolds created a fictional Italian state named Castelcicala to show working-class readers how a society founded upon Chartist principles would look in practice. But it was not merely a society founded upon the Six Points of the Charter that Castelcicala became but was instead ‘The Charter and Something More’: in Reynolds’s fictional Italian state there had been a political and a social revolution.[9]

The Charter and ‘Something More’

The Mysteries of London is undeniably a Chartist text. Throughout volumes 1–4 Reynolds makes several digressions from the plot to give his opinion on contemporary political matters. As the ‘monster meeting’ of Chartists at Kennington Common in April 1848 drew near, Reynolds declared in the issue for that week that

In order that the people may have a fair representation, the following elements of a constitution become absolutely necessary:—

Universal suffrage;

Vote by Ballot;

No Property Qualification;

Paid Representatives;

Annual Parliaments; and

Equal Electoral Districts.

Give us these principles—accord us these institutions—and we will vouch for the happiness, prosperity, and tranquillity of the kingdom.[10]

These aims were, of course, the same ones which Chartist activists campaigned for.[11] In other parts of The Mysteries of London Reynolds also reprinted the speech he gave to listeners at a political rally in Trafalgar Square.[12] Reynolds actually gave another speech at the Chartist Rally at Kennington Common that was also republished in Reynolds’s literary magazine, Reynolds’s Miscellany.[13] A national movement of working-class men and their allies in the middle classes,[14] the Chartists mounted three petitions in 1838, 1842, and in 1848. Reynolds was actually a late convert to the Chartist cause; in 1843, he argued in A Sequel to Don Juan that it was pointless to give uneducated men the vote.[15] However, by 1848 he was a changed man: the only answer to society’s ills, by that time, was to convince the government to draw up a constitution based upon Chartist principles. And working-class readers appear to have regarded Reynolds with some fondness. As Henry Mayhew recorded:

What they [working-class readers] love best to listen to — and, indeed, what they are most eager for — are Reynolds’s periodicals, especially the ‘Mysteries of the Court’ … I’m satisfied that, of all London, Reynolds is the most popular man among them. They stuck to him in Trafalgar Square, and would again. They all say he’s ‘a trump’.[16]

Even after the rejection of the 1848 petition Reynolds continued to campaign for democracy. Reynolds made several speaking tours throughout the country in the early 1850s where he spoke to Chartist activists who still quite clearly thought that there was something left to fight for.[17] In the run-up to the passage of the Reform Act (1867) Reynolds was instrumental in founding the National Reform League. Clearly the establishment of democracy in Britain was a cause close to his heart, even if some contemporaties and even modern scholars have cast doubt on his sincerity.[18]

After the rejection of the 1848 petition Reynolds, in tandem with other Chartist activists, also wanted to gain ‘the Charter and something more’.[19] Encapsulated in this idea was the aim to achieve the six points of the Charter but also to implement the nationalization of the land, the establishment of a national system of primary, secondary, and tertiary education, as well as reforms to the criminal justice system. Reynolds’s desire in this regard is expressed through the actions of the good Earl of Ellingham.

There is something of the ‘radical duke’ Charles Lennox, 3rd Duke of Richmond, in the character of the Earl of Ellingham; in him we have a nobleman who cares about, and seeks to ameliorate, the dire condition of the poor. In his youth, much like Lennox did in 1780,[20] Ellingham brings a bill into the House of Lords calling for the granting of universal suffrage, taxation, legal and educational reforms, and the establishment of a fixed minimum rate of wages:

The noble Earl then summed up his arguments by stating that he was anxious to see measures adopted for a minimum rate of wages, to prevent the sudden fluctuation of wages, and to compel property to give constant employment to labour:—he was desirous that indirect taxes upon the necessaries of life should be abolished;—he wished the laws and their administration to be more equitably proportioned to the relative conditions of the rich and the poor;—he insisted upon the want of a general system of national education, to be intrusted to laymen, and to be totally distinct from religious instruction and sectarian tenets;—he desired a complete reformation in the system of prison discipline, and explained the paramount necessity of founding establishments for the purpose of affording work to persons upon leaving criminal gaols, as a means of their obtaining an honest livelihood and retrieving their characters prior to seeking employment for themselves;—and he hoped that the franchise would be so extended as to give every man who earned his own bread by the sweat of his brow, a stake and interest in the country’s welfare. The noble Earl wound up with an eloquent peroration in which he vindicated the industrious millions from the aspersions, misrepresentations, and calumnies which it seemed to be the fashion for the upper classes to indulge in against them; and he concluded by moving a number of resolutions in accordance with the heads of his oration.[21]

The speech is received with the derision one might expect from members of the Victorian House of Lords. Never one to miss an opportunity to snipe at the philosophy of Edmund Burke, Reynolds tells us that one lord present rose and

Entirely blinking all the main arguments, he declaimed loudly in favour of the prosperity of the country—dwelt upon the happiness of English cottagers—lauded the “wisdom of our ancestors”—uttered the invariable cant about our “glorious institutions”—spoke of Church and State as if they were Siamese twins whom it would be death to sever—and, after calling upon the House to resist the Earl of Ellingham’s motion, sate down.[22]

The Earl’s motion does not carry and Ellingham did indeed foresee this result. However, his efforts do win him the applause of his working-class countrymen for when he exits parliament, ‘Then arose a shout … it was the voice of a generous and grateful people, expressing the sincerest thanks for the efforts which the noble patriot had exerted in their cause’.[23]

In the world of The Mysteries of London, it would not be in England where these enlightened democratic principles were implemented. Instead it was in Castelcicala that Reynolds set out his grand vision of the ideal society which applied Chartist principles in practice. The ‘Second Series’ jumps forward in time from the 1820s to the late 1840s when the undisputed hero of the ‘First Series’, Richard Markham, has become the Grand Duke of Castelcicala. The hero receives a hero’s welcome when he returns to Britain and, after the pomp and ceremony of meetings with British ministers of state, dines at the home of the Earl of Ellingham. Markham gives a speech at the dinner table in which he outlines the Chartist and Proudonian democratic and social reforms he has implemented in that country.

Yet first it must be asked—why did Reynolds choose Italy? In the real world, with Italy being a collection of individual sovereign states with differing forms of government, many of which were unstable despotisms, it was quite conceivable that a government in one of them could change overnight (and nineteenth-century novels did aspire to represent reality). Furthermore, some areas of Italy were hotbeds of insurrectionary activity. Nationalism was on the rise and, after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, the Carbonari—a network of revolutionary societies—had been busy coordinating uprisings against Ferdinand I, who ruled Naples, in 1821, and against the Savoy rulers in Piedmont-Sardinia in 1831.

After the revolution of 1831 failed the ringleaders of the Carbonari were arrested, some were put to death, others fled abroad—among those who fled abroad was Mazzini, who by 1837 was living in London.[24] Mazzini, a self-proclaimed visionary who founded The Friends of Italy, became a favourite with British liberals and republicans.[25] It is not known whether Reynolds or Mazzini ever met although we might speculate that they did. In an editorial Reynolds mounted a vehement defence of Mazzini after some of the Tory papers hurled the ‘basest misrepresentations’ against him.[26] But even if they did not meet, it is easy to see how Mazzini’s own ideology—Mazzini believed that ‘the people’ should mount a collective struggle to establish a unified Italian republic—would resonate with Reynolds, who was an outspoken republican and in the late 1840s became active in the Chartist movement.[27]

Given the ‘real world’ possibilities that Italy could be reshaped into a progressive republic, the fictional Italian state of Castelcicala was an ideal ‘laboratory’ through which Reynolds could represent a Chartist republic being founded in ‘real time’ in a believable setting. A lot of the Chartist fiction written by British writers either looked back to pre-modern times and bewailed the Anglo-Saxons’ loss of rights under the Normans—as Thomas Miller does in Royston Gower; or, The Days of King John (1838) and Pierce Egan in Wat Tyler: The Rebellion of 1381 (1842)—or they looked forward to a far-off future state when the British constitution would finally be remoulded along Chartists lines—such is the message of The Political Pilgrim’s Progress (1839).[28] Other writers may have drawn attention to the hideous poverty faced by the working class, as Ernest Jones did in Woman’s Wrongs (1852) and Reynolds likewise did this in The Seamstress; or, The White Slave of England (1853).[29] In the latter novel the heroine Virginia Mordaunt’s life is one of unremitting struggle and poverty—there is no end in sight to this and she does indeed die penniless.

These ‘poverty’ novels did not show how the social problem of poverty could be resolved by the achievement of working-class suffrage. This is where Reynolds’s Mysteries of London was truly different. Reynolds’s novel was never central to Chartist culture. Instead the movement’s main literary output was newspapers and poetry, the latter which, as Mike Sanders has shown in The Poetry of Chartism (2009), was usually printed in the newspapers.[30]

There are (to my knowledge) no Chartist novels depicting the overthrow of the British political establishment and the implementation of a new society based upon the Charter; novels in the nineteenth century were supposed to represent ‘real life’, and having Markham lead an army to overthrow Queen Victoria—who features as a character in Reynolds’s novel—simply would not have been believable. But having a progressive society being founded in one of the small Italian kingdoms—several of which were hotbeds of insurrectionary activity—was more believable.

A Throne Surrounded by Republican Institutions

To return, then, to Richard Markham’s speech at the Earl of Ellingham’s mansion, the constitution of Castelcicala is described as ‘a Throne Surrounded by Republican Institutions’. Markham may have been elevated to the rank of a prince, yet he is modest and not ostentatious:

The Prince of Montoni [Markham] was dressed in plain clothes: but on his breast gleamed the star denoting his rank; and on his left leg he wore the English Garter.[31]

It is through Markham’s personal merits that he distinguished himself in life and he has no need to make showy displays of wealth and rank. After the dinner has ended and the ladies present, in true Victorian style, have retired from the table—for of course they would not be interested in politics—the conversation turns to constitutional matters when

The Earl of Ellingham questioned the Prince relative to the condition of the Castelcicalans, whom report, newspapers, and books represented to be in the highest possible state of civilisation prosperity, and happiness.[32]

The prosperity and happiness enjoyed by the citizens of Castelcicala is accounted for by the fact that something similar to the Chartist program has been practically implemented there in full. As Markham says:

The people have the elections entirely in their own hands, and return to Parliament representatives who do not buy their seats, but who are chosen on account of their merits. At least, this observation applies to the great majority of the Senators and Deputies. The elections take place every two years; so that ample opportunity is allowed the constituents of getting rid of persons who may chance to deceive them or prove incapable; while a sufficient space of time is afforded for giving the representatives a fair trial. The result of these arrangements is, that the majority of the representatives legislate for the interests of the mass—and not of the few. Good measures are the consequence; and the happiness of the people is promoted, while civilisation progresses rapidly, and the prosperity of the country increases daily. My lord,” continued the Prince, turning towards the Earl of Ellingham, “history has recorded the memorable speech which your lordship delivered nineteen years ago in the House of Lords—the speech that first introduced your lordship to the world as the generous defender, vindicator, and champion of the People;—and it rejoices me unfeignedly to be enabled to inform you, my noble friend—for so you will permit me to call you—that the speech I allude to, and all your subsequent orations on the same subject have been studied, weighed, and debated upon in the Councils of the Sovereign of Castelcicala.[33]

(For more information on the Victorian political system, my article on the Victorian Web gives a summary of Victorian voting practices, while a previous post of mine examined voting practices prior to 1832).

The implementation of the Chartist programme in Castelcicala, however, was only the first stage in what has effectually been a social revolution. It is in Markham’s delineation of the changes in the social constitution of the Castelcicalan state that we find the presence of St Simonian and Proudhonian thinking, combined with his own ideas. Reynolds was a passionate promoter of working-class education, and in Castelcicala all primary, seconday, and tertiary education is free to all and entirely secular: there was a national system of education. This thinking was in line with that of Mazzini and Mikhail Bakunin.[34] Reynolds was not simply anticipating the paltry provisions enshrined in the later Education Act of 1870, which only mandated free compulsory education to children but wanted a truly comprehensive system in order that all people could achieve intellectual fulfilment. Reynolds continued to campaign for a national system of education, as he stated in 1853:

All the universities, colleges, and schools should be supported by the state, the education they afford being gratuitous.[35]

In this Reynolds went further than some of his socialist contemporaries like Proudhon, whom said little about educational provision beyond stating that it was valuable because teachers—broadly defined—are in effect ‘cultivators of the land’ because it is they who in a mutualist society would not only consume the surplus products of producers but were also the guardians of knowledge.[36] It was the teachers and members of ‘all arts and trades’ who knew how to teach people, for example, how to use machinery and tools correctly.

While many Victorians in the age of laissez-faire capitalism would have balked at the projected cost of a scheme for national education, Reynolds assured them that society would gain in other ways if his plan was set in motion. An educated population would, in theory, mean that fewer people would have to be maintained at the state’s expense in the gaols, the prison hulks, and the penal colonies. The likes of Reynolds’s menacing Resurrection Man from the Mysteries of London would become a thing of the past because, along with the franchise, it would give people a stake in society, and greater numbers of people would be less-inclined to break the social contract.

However, Reynolds’s vision of a just society went beyond merely giving everyone an education. In Castelcicala

a fixed minimum for wages has been established—the lowest amount of payment ensuring a sum sufficient to enable the working man to maintain himself and his family in respectability.[37]

There has of course been a long history in the United Kingdom of wage regulation and arguments for and against it. As far back as the Statute of Labourers in 1351, a maximum wage for certain industries was passed into law. King James I in 1604 signed into a law an act that mandated a fixed minimum rate of wages for textile workers. Adam Smith’s ambiguous remarks, whereby he stated that wages should always be of a sufficient amount to support labourers, have been taken by some scholars to mean that he was in favour of a fixed minimum rate of wages.[38] In the Victorian era arguments for and against a minimum rate of wages had been known for some time. John Stuart Mill critiqued these arguments in Principles of Political Economy (1848), the same year that Reynolds was writing the Second Series of The Mysteries of London.

Yet even with a minimum wage, how would the Castelcicalans break up the political influence of its propertied oligarchy? Reynolds set his sights on primogeniture. Primogeniture, the law by which the eldest son or eldest male relative inherited the family property when the father died intestate, was alive and well in Victorian England. Even where fathers did not die intestate the principle of primogeniture was the norm when any father wrote his will, perhaps with some codicil making provision for the other siblings. There were many Victorian novels in which the actions of certain characters are motivated by the existence of this practice; many female characters are courted by penniless young gentlemen in such novels because, where a rich father had only a daughter to bequeath money to, were she to marry the estates would pass to her husband. The law of primogeniture would not be abolished until 1925 but in Castelcicala in the 1840s it has already been abolished. Under Markham’s reign a man’s property, after he dies, must be divided equally between his children:

no man can leave his estate solely to his eldest son; it must be divided amongst all his male children equally, a charge being fixed upon it for the support of his daughters.

It was not only in The Mysteries of London that Reynolds promoted the abolition of primogeniture; he consistently promoted its abolition throughout his writing career, reasoning in ‘The Revival of a Working-Class Agitation’ that it was ‘abhorrent’ to ‘principles of common justice’.[39] This harks back to the Saint-Simonians who asked: by virtue of what authority does the present proprietor enjoy his wealth and transfer it to his successors?

The Saint-Simonians’ answer to this question was as follows:

By virtue of legislation, the principle of which goes back to conquest, and which, however distant it may be from the source, still manifests the exploitation of man by man, of the poor by the rich, of the industrious producer by the idle consumer: the advantages which property confers, whether it comes from inheritance or is acquired through labor, are thus only the delegations of the rights of the stronger, transmitted by the accident of birth, or ceded to the labourer under certain conditions.[40]

J.P. Proudhon, whose work Reynolds described as ‘thrilling’ when he endorsed it in Reynolds’s Political Instructor,[41] likewise echoed these Saint-Simonian sentiments. In What is Property (1840) Proudhon took issue with the idea of primogeniture by stating that

as regards donations, wills, and inheritance, society, careful both of the personal affections and its own rights, must never permit love and partiality to destroy justice … society can tolerate no concentration of capital and industry for the benefit of a single man’.[42]

Thus instead of a small number of people inheriting land and property while the great mass of people were excluded, as happened in Britain, the effect of the abolition of primogeniture in Castelcicala is to give each person a stake in the country which, gradually, would erode the landed oligarchy’s dominance.

Reynolds was a socialist. In time he would advocate for the nationalisation of all industries and farmland (though these features do not form a part of the Castelcicalans’ society). He was, of course, a pre-Marxist socialist and his Italian Chartist republic is very idealistic—achieved merely through a short revolution in which all the Castelcicalans welcome their new ruler with open arms. Reynolds’s vision of a new Chartist Italian society was certainly not original in terms of what it portrayed; several of the tenets that Reynolds outlined in this section of this book were elucidated in the works of several writers who had gone before. Moreover, Reynolds’s vision lacked the ‘scientific’ underpinning that Karl Marx would later give to establishment of socialism. Yet as one of the biggest-selling authors of the Victorian era he was a prominent voice who amplified progressive politics, and to my knowledge he was the first Chartist novelist who grappled with the question of what a Chartist state would look like in practice.

Of course, one perhaps wonders how Reynolds’s fictional Italian state could ever truly be called socialist if it had a monarch like Richard. But just like the great republican hero of Ancient Rome, when all of these reforms to society have been implemented Markham voluntarily lays down his crown and proclaims a republic. The fictional Castelcicala becomes Europe’s first truly democratic republic and Reynolds wish was that, in the real world, Britain would follow suit.

Of course, even just twenty years later Reynolds’s fictional petty kingdom of Castelcicala would be unrealistic to new readers. Italy was unified (or conquered) by the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia in 1860. The new Italian state, although it was a constitutional monarchy with a parliament based on a limited franchise, was hardly progressive. In fact, it took many years for the new Piedmontese rulers to suppress resistance to its rule in the south of Italy. Italy would never be the progressive state that Reynolds envisioned and as for England, true universal suffrage would not be achieved until 1918.

References

[1] The most up-to-date biography can be found in Anne Humpherys and Louis James, ‘Introduction’, in G.W.M. Reynolds: Nineteenth-Century Fiction, Politics, and the Press, ed. by Anne Humpherys and Louis James, 2nd edn (Abingdon: Routledge, 2019), pp. 1–18.

[2] The following are translations of French literature that can be definitely attributed to Reynolds: Victor Hugo, Songs of Twilight, Trans. G.W.M. Reynolds (Paris: Librarie des Estrangers, 1836); G.W.M. Reynolds, The Modern Literature of France, 2 vols (London: George Henderson, 1839); Victor Hugo, The Last Day of a Condemned, Trans. G.W.M. Reynolds (London: George Henderson, 1840); Paul de Kock, Sister Anne, Trans. G.W.M. Reynolds (London: George Henderson, 1840). However, in G.W.M. Reynolds, Wagner the Wehr-Wolf, ed. by E.F. Bleiler (New York: Dover, 1975), p. 158 Bleiler points out there are several further translations of French novels likely completed but which cannot be ascribed definitely to Reynolds due to the usual practice of publishers’ practice of not crediting translators personally.

[3] G.W.M. Reynolds, ‘The Sculptor of Florence’, The Monthly Magazine, November 1838, 525–36.

[4] Anon. ‘Joseph Mazzini’, Reynolds’s Political Instructor, 27 November 1849, 17–18.

[5] Richard Maxwell, The Mysteries of Paris and London (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1992).

[6] Stephen Basdeo, ‘ “That’s Business”: Organised Crime in G.W.M. Reynolds’ The Mysteries of London (1844–48)’, Law, Crime and History, 6: 2 (2018), 53–75; Stephen James Carver, ‘The Wrongs and Crimes of the Poor: The Urban Underworld of The Mysteries of London in Context’, in Humpherys and James, pp. 147–60.

[7] G.W.M. Reynolds, The Mysteries of the Court of London, 8 vols (London: John Dicks, 1849–56), VIII, p. 412.

[8] Christopher Duggan, A Concise History of Italy (Cambridge University Press, 1994), pp. 87–116.

[9] A previous attempt to map Reynolds’s political ideology can be found in Rohan McWilliam, ‘The Mysteries of G.W.M. Reynolds: Radicalism and Melodrama in Victorian Britain’, in Living and Learning: Essays in Honour of JFC Harrison, ed. by Malcolm Chase and Ian Dyck (London: Scolar Press, 1996), pp. 182-98.

[10] G.W.M. Reynolds, The Mysteries of London, vols 1–4 (London: G. Vickers, 1844–48), IV, p. 233.

[11] Dorothy Thompson, ‘Who were “the people” in 1842?” in The Dignity of Chartism, ed. by Stephen Roberts (London: Verso, 2015), pp. 21–42 (p. 25).

[12] Reynolds, The Mysteries of London, IV, pp. 201–02.

[13] G.W.M. Reynolds, ‘The Editor’s Speech at the Monster Meeting at Kennington Common’, Reynolds’s Miscellany, 3: 74 (1848), 326.

[14] Thompson, ‘Who were “the people” in 1842?” p. 25.

[15] G.W.M. Reynolds, A Sequel to Don Juan (London: Paget, 1843), p. 33.

[16] Henry Mayhew, London Labour and the London Poor, 4 vols (London: Frank Cass, 1967), I, p. 25.

[17] G.J. Harney, ‘Political Postscript’, Democratic Review, March 1850, 399.

[18] Karl Marx, ‘Marx to Engels, October 8, 1858’, in John Saville, Ernest Jones: Chartist (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1952), p. 242. Of Reynolds Marx said that he was ‘a much bigger rascal than [Ernest] Jones, but he is a rich, and an able speculator’. Louis James, Fiction for the Working Man, 1830–1850: A Study of Literature Produced for the Working Classes in Early Victorian England, 2nd edn (London: Penguin, 1973), p. 197. As Louis James, in my opinion, unfairly says of Reynolds: ‘His radicalism serves a dramatic rather than a genuinely social purpose, and is finally subject to the conventions of romance … The lower classes are made up of thugs, resurrection men, fences, prostitutes, or starving paupers … Reynolds’s social criticism is overbalanced by his sensationalism’.

[19] G.J. Harney, ‘The Charter, and Something More’, The Democratic Review, February 1850, 349.

[20] Charles Lennox, The Bill of the Late Duke of Richmond for Universal Suffrage and Annual Parliaments (London: William Hone, 1817), p. 1.

[21] Reynolds, The Mysteries of London, III, p. 370.

[22] Ibid., p. 371.

[23] Ibid., p. 371.

[24] For more information on Mazzini and his writings see the following: Stefano Recchia and Nadia Urbinati, eds. A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini’s Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International Relations (Princeton University Press, 2009).

[25] Enrico Verdecchia, Londra dei cospiratori. L’esilio londinese dei padri del Risorgimento (Milan: Marco Tropea Editore, 2010), p. 36.

[26] G.W.M. Reynolds, ‘Kossuth, Mazzini, and Ledru-Rollin’, Reynolds’s Political Instructor, 29 December 1849, 58.

[27] Duggan, p. 108.

[28] See Stephen Basdeo, ‘The Chartist Robin Hood: Thomas Miller’s Royston Gower; or, The Days of King John (1838)’, Studies in Scottish Literature, 44: 2 (2018), 72–81; Stephen Basdeo, The Life and Legend of a Rebel Leader: Wat Tyler (Barnsley: Pen and Sword, 2018); and Thomas Doubleday, ‘The Political Pilgrim’s Progress’, in Chartist Fiction, ed. by Ian Heywood (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), 1–64.

[29] For a general overview of Chartist fiction see the following: Rob Brereton and Gregory Vargo, eds [online], Chartist Fiction Online, accessed 13 August 2018. Available at: http://chartistfiction.hosting.nyu.edu/home.

[30] For a critical discussion on the poetry of Chartism see the following: Mike Sanders, The Poetry of Chartism: Aesthetics, Politics, History (Cambridge University Press, 2009).

[31] Reynolds, The Mysteries of London, IV, p. 88.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Giuseppe Mazzini, cited in Colin Ward, Anarchy in Action, rev. ed. (London: Left Book Club, 2020), p. 93.

[35] G.W.M. Reynolds, ‘The Government System of Education’, Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper, 10 April 1853, 1.

[36] P.J. Proudhon [online], What is Property? An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and Government (1840), accessed 9 September 2020. Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org.

[37] Reynolds, The Mysteries of London, IV, p. 90.

[38] Betsy Jane Clary, ‘Smith and Living Wages: Arguments in Support of a Mandated Living Wage’, The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 68: 5 (2009), 1063–84

[39] G.W.M. Reynolds, ‘The Revival of Working-Class Agitation’, Reynolds’s Political Instructor, 10 November 1849, 1–2.

[40] Georg G. Iggers, Trans. Doctrine of St-Simon: An Exposition. First Year, 1828–1829 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958), pp. 92–93.

[41] G.W.M. Reynolds, ‘Property’, Reynolds’s Political Instructor, 26 January 1850, 90.

[42] P.J. Proudhon [online], What is Property?

Excellent analysis Stephen. I haven’t explored that angle yet. I have been concentrating on the fairy tale aspect more. It seemed to me that the fairy tale was meant to appeal more to the women.

Let us assume that Reynolds was being calculating. There were paid readers who read the installments to the illiterate. It is quite probable that the Chartists sought that role and, if so, they probably explained the story to their listeners much as you have done here. Remember that Reynolds named one of his publicatons The Political Instructor. Possibly the readers were the instructors. The Chartist position then would have been broadcast wildly, thus the turnout in 1848. As the guilty party Reynolds would have been a marked man by the authorities.. They would have been dogging his foot steps while needing a man inside his organization. I am becoming of the opinion that his printer John Dicks was that man.