By Stephen Basdeo

The Victorians in many ways were just like us: they enjoyed a good scandal whenever it was reported in the press, they liked both trashy and high-brow entertainment, and like today, they had their popular heroes adored by both adults and children. Let me introduce you to the Harry Potter of the late-Victorian era: Mr Jack Harkaway.

Harkaway was not a real person but a fictional character, immortalised in countless novels and boys’ adventure magazines. And when I say he was popular, I am not exaggerating.

Jack Harkaway

It is hard for us at a distance of over a century to appreciate just how popular Harkaway was with younger readers; in many ways he was the Harry Potter of the late-Victorian period, a character who basked in worldwide fame. So high was demand among newsagents for the latest instalment of a Jack Harkaway, a ‘penny dreadful’ serial, that (allegedly) they battled with each other outside the Edwin J. Brett’s offices—the publisher of The Boys of England—to obtain copies which they could then sell to their younger customers.[i] Hemyng’s first Harkaway serial, entitled Jack Harkaway’s Schooldays was originally published in 1871 in the columns of Brett’s The Boys of England, a penny magazine for younger readers.

Harkaway stories were originally serialised in The Boys of England

Within months, the publishers of The Boys of England knew that they were on to a hit: it had already appeared in the United States in several periodicals by the end of that year, and two years later it was being reprinted in both the United Kingdom and the United States in different magazines. The London-based publisher Hogarth House decided to then issue the first run of serials in clothbound library editions, while similar publishers in America decided to follow suit.

Harkaway’s adoptive father, Prof. Mole.

It should be said here that, although the original Jack Harkaway stories were serialised in The Boys of England, it was only children who read of Harkaway’s exploits. Just like Harry Potter today, both children and adults devoured his books. Newspaper and magazine advertisements publicising the release of the latest Harkaway novel, for example, declared that ‘every boy and man should read and have in their possession in a complete form Jack Harkaway’s Schooldays’.[ii]

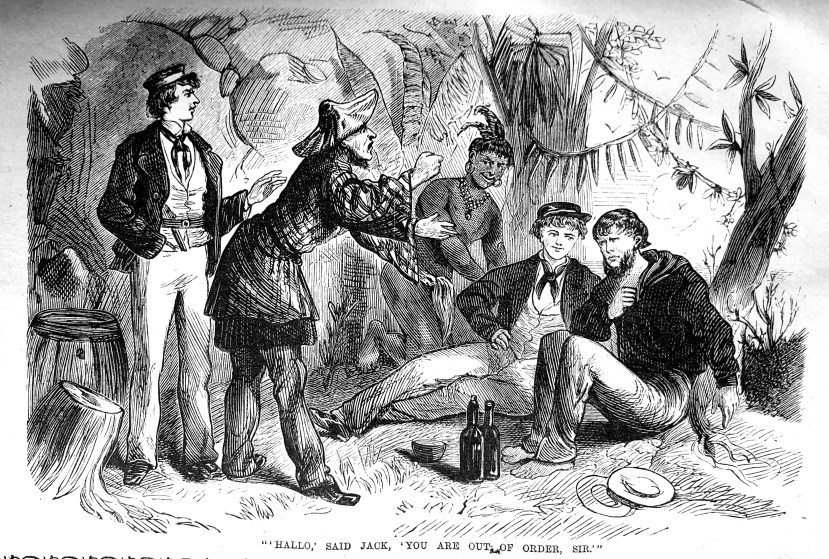

Jack’s best friend was a man named Monday

Harkaway was still fondly remembered by some newspaper correspondents as late as the 1960s, when he was described in The Times as ‘a character dear to boyish readers’.[iii] And even in 2000, Keith Waterhouse in the Daily Mail fondly recalled reading reprints of these penny dreadfuls, although he oddly likened the-then British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, to Jack Harkaway.[iv]

Recent scholarship from Theresa Michals has investigated the blurred lines between those works which literary critics have traditionally thought of as children’s literature were read by many adults. The situation is further complicated by the fact that many adult novels were republished in children’s editions. Michals concludes that many late-Victorian novels were written for ‘children of all ages’, just like, as The Times’s correspondent said of Harkaway in the 1960s, that he was a figure for ‘boyish’ readers—those whose reading tastes might be considered immature—instead of just boys, much like those grown up but rather immature men today read Harry Potter.[v]

Although Hemyng originated the character, having been kept extremely busy writing four Harkaway serials between 1871 and 1874, he soon after laid down his pen and other, now anonymous, authors carried Jack’s adventures further afield. Besides, even though Harkaway’s success had allegedly managed to propel sales of The Boys of England to over 250,000 copies per issue, Hemyng would not have benefitted from this popularity due to the flat fee payment system used by Brett and many other penny publishers.[vi] In the twentieth century some American critics doubted that Hemyng was the original author of the work as it was originally published anonymously.[vii] The tales published in Britain were available for sale in the USA and those printed in the USA were available in England, so it was rather unclear, by the early 1900s, if he was a British hero or an American hero. And once the American writers took over, they were not that bothered about continuity between the various stories. Jack could be visiting Cuba in one serial and be in America in another.

While Harkaway’s success has been studied before in terms of its importance in the history of the penny dreadful publishing industry, he remains a figure whose novels are more often cited rather than actually read, usually with a view to investigating Harkaway’s place in the late nineteenth-century moral panic over penny dreadfuls.[viii] Few indeed, if any, articles have ever subjected the text of the serials to in-depth critical review; the serials are often cited but rarely read and this is something which this chapter hopes to partially remedy. After all, a serial which allegedly sold over 250,000 copies, which appealed to readers of all ages, ought not to be overlooked.

But let’s have a brief overview of this lad’s life and deeds.

Unlike the heroes of the five shilling popular novels, who were usually the son of some aristocrat or upper middle class family, Harkaway’s origins were a little more humble: he was an orphan who was raised in a school for poor children. As he entered his teenage years, he grew increasingly tired of being made to learn so he ran away from school, boarded a ship, and set off on an adventure.

In time, he acquired a servant called Monday, who was obviously based on Defoe’s Man Friday from Robinson Crusoe (1719). The professor and explorer, Dr Mole, also took young Jack under his wing. The exploits of this trio took them around the world. Mole was there to provide the adult advice to Harkaway when he needed it, especially because he was fond of playing pranks on people and generally being an annoyance to those who met him, and Monday was there as the faithful servant who would give his life to save Jack in any situation.

Sometimes Harkaway’s pranks backfired on him somewhat, such as the time he had to do battle with a 15ft python. Professor Mole, Harkaway, and Monday once joined the crew of a sailing ship in the West Indies, but Jack learns that a scientist has brought a large snake on board as a specimen to study when they return to England. Ever reckless, he decides that he will release the snake from its box and then prank his professor by telling him someone wants to see him down below. It does not go as planned for the snake was

Fully fifteen long … the snake, astonished at his unexpected freedom, raised his ugly head and glared savagely at Jack, who picked himself up and retreated to a safe distance.

“Morning, Governor,” he said, nodding his head, “how do you find yourself?”

The python’s only reply to this was to uncoil himself and glide out of his box on to the floor. Jack was rather astonished at his prodigious size; he did not think he was half so big or formidable, and was rather sorry he’d let him out.[ix]

When the crew were alerted to the fact that the snake had escaped, they were clear that it was Jack’s problem for him to sort out. So he had to go in and decapitate the poor thing.

And they did get into some pretty hair-raising situations: Harkaway became the scourge of pirates and bandits the world over. In Italy, he ensured the apprehension of a notorious outlaw named Barboni.

Although he was a rascal, he had a good heart and would do anything for his friends. He had a deep hatred for the Boers, however, whom he regarded as racist, and when the Boer War broke out, he enthusiastically enlisted to serve his country. in Jack Harkaway in the Transvaal: or, Fighting for the Flag (1900), set during Boer War. When Jack captures a lone Boer, he does not pass up a chance to humiliate his captive by making him sing English patriotic songs:

“…Don’t get up. Keep on your knees; I like to see you that way. Now, follow me, pay attention: say ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘God Save the Queen.’”

“What!” cried [the Boer] … “Here you are. ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘God Save Your Queen.’ Ugh! There is a lump in my throat. You make me sick. That Queen sticks. She will choke me. I say it, but don’t mean it.”

“Now, sing it,” continued Jack, putting the rifle a few inches nearer to his head. “I set you a go. Don’t mumble, but raise it. Give us a chest note. ‘Send her Victorious, happy and glorious, long to reign over us, God Save the Queen.’”

With the utmost reluctance, and making as many grimaces as a monkey with the spasms, the Boer followed Jack, and then rolled on the floor, burying his face in his hands.

“Hurrah! That’s your sort. Bravo our side. ‘Rule Britannia, Britannia rules the waves, and the Transvaal Boers shall never make us slaves.’”[x]

Where Jack’s original adventures took him to deserted islands and mainly British colonies, American authors had him gallivanting all over China, Cuba, Greece, and of course the United States, where he meets with Native Americans and spends some time living on the prairies.[xi]

Eventually, after a long life at sea and getting into scrapes, Jack married his childhood sweetheart. They had a son together but one novelist killed off his wife and then set the stage for a series of adventures featuring both Jack Harkaway and his son.

And, if you look closely at the cover for my forthcoming book, Heroes of the British Empire (2020), you’ll see this guy has pride of place!

Cover for my forthcoming book Heroes of the British Empire (2020), in which Jack Harkaway is given pride of place on my front cover.

Notes

[i] Christopher Mark Banham, ‘Boys of England and Edwin J. Brett’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Leeds, 2006), p. 61.

[ii] ‘Advertisements and Notices’, The Illustrated Police News, 1 February 1873, 4.

[iii] ‘The Most Exciting Boat Race: No Wonder Jack Harkaway Felt a Bit Baked After Oxford’s Win’, The Times, 31 March 1960, 14.

[iv] Keith Waterhouse, ‘Blair’s Bound to Please in Brighton’, Daily Mail, 28 September 2000, 14.

[v] Teresa Michals, Books for Children, Books for Adults: Age and the Novel from Defoe to James (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014), p. 128, p. 135.

[vi] ‘Jack Harkaway’s Creator’, Daily Mail, 20 September 1901, 3.

[vii] Banham, ‘The Boys of England and Edwin J. Brett’, p. 60.

[viii] John Springhall, ‘A Life Story for the People? Edwin J. Brett and the London “Low-Life” Penny Dreadfuls of the 1860s’, Victorian Studies, 33: 2 (1990), 223–46; John Springhall, Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics Penny Gaffs to Gangsta-Rap, 1830–1996 (London: MacMillan, 1998), pp. 38–97; Louis James, Fiction for the Working Man, 1830–50: A Study of the Literature Produced for the Working Classes in Early Victorian Urban England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1963) pp. 159–60;

[ix] Bracebridge Hemyng, Jack Harkaway After Schooldays (London: Publishing Office, 1873), 25–6.

[x] Bracebridge Hemyng, Jack Harkaway in the Transvaal: or, Fighting for the Flag (London: Harkaway House, 1900), p. 55

[xi] J. Randolph Cox, The Dime Novel Companion: A Source Book (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2000), pp. 129–30.