For Pen and Sword Books I am producing a new annotated edition of The Comic History of England (originally published in 1846). I thought I’d give readers a taste of what this fine book has to offer.

In George W.M. Reynolds’s best-selling novel The Mysteries of London (1844–48), a butler, a lawyer, and a parson are congregated in a public house. The three of them strike up a conversation with a bookseller, for the parson reveals that he has written a new romance—a tale in which vice is punished and virtue is rewarded!

The bookseller tells the parson not to bother taking his book to a publisher:

“Ah!” said the bookseller, after a pause; “nothing now succeeds unless it’s in the comic line. We have comic Latin grammars, and comic Greek grammars; indeed, I don’t know but what English grammar, too, is a comedy altogether. All our tragedies are made into comedies by the way they are performed; and no work sells without comic illustrations to it. I have brought out several new comic works, which have been very successful. For instance, The Comic Wealth of Nations; The Comic Parliamentary Speeches; The Comic Report of the Poor-Law Commissioners, with an Appendix containing the Comic Dietary Scale; and the Comic Distresses of the Industrious Population. I even propose to bring out a Comic Whole Duty of Man. All these books sell well: they do admirably for the nurseries of the children of the aristocracy. In fact they are as good as manuals and text-books.”

These remarks in Reynolds’s book were a nod to Gilbert Abbot á Beckett’s corpus of ‘comic’ history books which included The Comic History of England, as well as The Comic History of Rome and The Comic Blackstone, the last of which was a satirical law textbook which lampooned William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (originally published in four volumes in 1765).

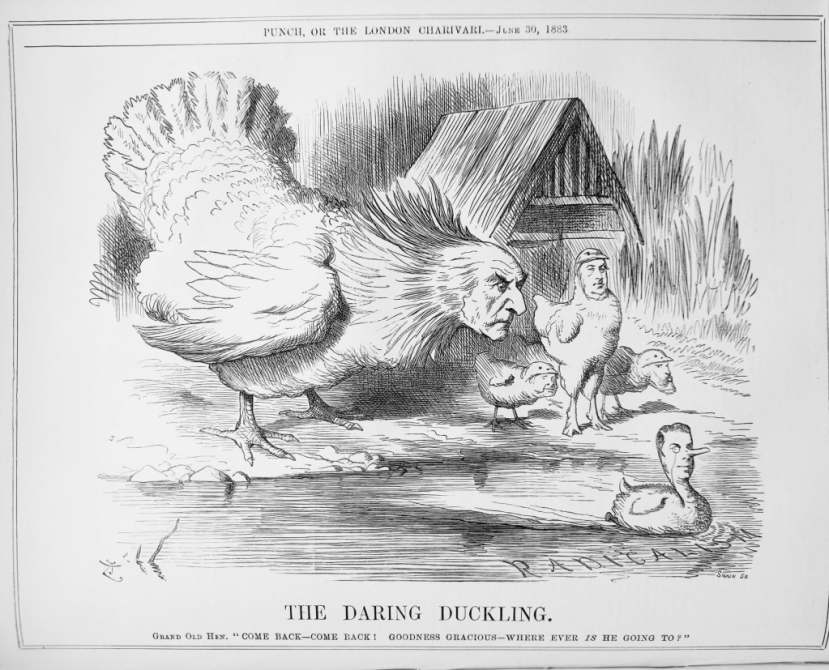

People from the nineteenth century appear to us, in surviving portraits and photographs, often as stern and pompous people. Yet they liked to laugh. The novels they read made them laugh. Several magazines were printed with the intention of making their readers laugh—among these were Fun, Judy, The Man in the Moon, and last but certainly by no means least: the famous Punch. As Gilbert Abbot á Beckett’s Comic History of England shows us, they also laughed at their history.

Born in 1811 to a middle-class family in Wiltshire, young Beckett was educated at Westminster School and was destined for the legal profession. Although he was called to the bar he decided to pursue the career of a writer. He became a regular contributor to the The Times and also wrote ‘adaptations’ of Dickens’s novels. From Beckett’s pen flowed such classics as Oliver Twiss the Workhouse Boy (1839)—a blatant copy of Dickens’s Oliver Twist (1838)—and the Posthumous Papers of the Wonderful Discovery Club (1838), which was a thinly-veiled copy of Dickens’s Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1837). He also turned his attention to theatre writing and wrote several humorous plays before writing The Comic History of England.

Beckett’s Comic History of England was originally published in serial instalments in Punch in the latter half of 1846, and ended early in 1847. Founded in 1841 by social investigator Henry Mayhew and Ebenezer Landells, the magazine featured humorous short stories, jokes, and funny illustrations. Some of the Victorian era’s best writers made their mark in Punch, among these were the poet Thomas Hood and the novelist William Makepeace Thackeray.

In its early years Punch could, at times, be quite radical; many of its illustrations drew attention to social ills such as poverty, pollution, and the wrongs of the factory system. The magazine was therefore a suitable outlet for Beckett to contribute to for, in addition to his efforts as an author, Beckett was also a philanthropist and contributed to several government reports on social issues.

Politicians were also considered fair game for Punch writers and illustrators; a little later in the century William Ewart Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli or ‘Dizzy’, as the magazine affectionately called the latter, were routinely mocked. Not even the royal family was sacred—Queen Victoria was one ‘star’ of the magazine who regularly appeared as a cartoon in its columns. Although Punch faced some financial difficulties when it first started the magazine soon became a household name. As the historian Richard Altick notes:

To judge from the number of references to it in the private letters and memoirs of the 1840s … Punch had become a household word within a year or two of its founding, beginning in the middle class and soon reaching the pinnacle of society, royalty itself.

Although she was regularly portrayed in Punch’s columns Queen Victoria herself must have been amused indeed, and had no issue reading the magazine (perhaps she even secretly let out an unconstitutional chuckle when a politician she disliked was lampooned).

When the serial run of Beckett’s Comic History ended a one volume edition was quickly published and it was continually republished throughout the nineteenth century, and most editions retained John Leech’s fantastic illustrations.

Although at a basic level Beckett wanted to show that the writing of history could be funny while being factual—Beckett included footnotes indicating where his information came from—he also made a wider point. While a lot of early Victorian history writing was unashamedly patriotic and cast the actions of its historic rulers in a wonderful light, Beckett showed these historical statesmen up for what they really were: thugs and brutes who were often embroiled in scandals. Most of the ‘great men’ from English history were rarely worthy of admiration.

Beckett died in 1856 and his Comic History has been forgotten by modern audiences. I hope you enjoy the short snippet given below of the Peasants’ Revolt: a truly horrible history!

Stephen Basdeo (editor)

The king being now dead, the republican beggars were on horseback, and began at a rapid pace the ride whose terminus we need not mention. On the 5th of February, 1649, a week after the execution of Charles, the Commons had the impudence to vote the House of Peers “both useless and dangerous.” One of the next steps of the lower House was to vent a sort of brutal malignity upon unfeeling objects, and having no longer a king to butcher, it was resolved to break up all his statues. The Commons thought, no doubt, to pave the way to a republic by macadamising the road with the emblems of royalty.

Considerable discussion has been raised upon the question of the right of a nation to decapitate its king; and, of course, if the people may do as they please with their own, they may do anything. The judgment of posterity has very properly pronounced a verdict of “Wilful Murder” against the regicides, and we have no wish to disturb this very fair decision. It is very unlikely that a similar state of things will ever arise again in England; but, if such were to be unhappily the case, there are, in these enlightened times, numerous pacific and humane modes of meeting the emergency. “Between dethroning a prince and punishing him, there is,” as Hume well observes, “a wide difference;” and unless the professed humanity-mongers should get fearfully ahead—unless the universal philanthropists should gain an ascendency over public opinion—there is no fear that kings or aristocrats will ever be butchered again, for the promotion of “universal love” and “brotherhood.”

When Charles was no more, the republicans continued to show their paltry malevolence by making insulting propositions as to the disposal of his family. It was suggested that the Princess Elizabeth should be bound apprentice to a button-maker; but the honest artificer to whom the proposal was made generously hoped that his buttons might be dashed before he became a party to so petty an arrangement. Happily for the princess, death, by making a loophole for her escape, saved her from being reduced to the necessity of making buttons.

A Committee of Government had been hitherto sitting at Derby House, which was now changed into the Executive Council, with Bradshaw as president, and Milton, the poet, as his secretary: the latter having being employed no doubt on account of his powerful imagination to conceive some possible justification for the conduct of the regicides. Duke Hamilton, the Earl of Holland and Capel, the last of whom had bounded away like a stag, but was seized at the corner of Capel Court, were all tried and beheaded.

The usual consequences of the triumph of the “great cause of liberty,” as advocated by noisy demagogues, and of the ascendency of the soi-disant friends of the people, very soon became evident. It was declared treason to deny the supremacy of Parliament, which might indeed lay claim to supremacy in oppression, pride, and intolerance. The “freedom of the press” was completely stopped; and, in fact, there was the customary direct antagonism between principle and practice which too frequently marks the conduct of the hater of all tyranny except his own, and the ardent friend of his kind, which is a kind that we do not greatly admire.

The king’s eldest son was proclaimed as Charles the Second, in Scotland and Ireland, which caused Cromwell to say, “I must go and see about that,” and to start at once for Dublin. Having done considerable damage, notwithstanding the resistance of some of the Irish youth, who went by the name of the Dublin Stout, he left his son-in-law, Ireton, to look after Ireland, thinking, perhaps, he would be acceptable from the semi-nationality of his name, while he himself returned to England. He took up his abode in London, at a place called the Cockpit, where he was visited by several persons of consequence; and the new lord of the Cockpit enjoyed the Gallic privilege of having a good crow upon his own dunghill.

Montrose now made an attempt in Scotland in favour of Charles the Second, but being defeated, he fled and sought refuge with a Scotch friend, who, of course, sold him for what he would fetch, and made £2000 by the business transaction. Poor Montrose was hanged at Edinburgh, on a gallows thirty feet high, which justifies us in saying that cruelty was carried to an immense height, on this deplorable occasion. Charles himself now took the field, having landed at the Frith of Cromarty, and had collected a tolerably large army under Lesley. Cromwell instantly started for Scotland, with a considerable force, and attacked the royalists at Dunbar, where he encouraged his own troops by a quantity of religious cant, which contrasted strangely with the sanguinary nature of his object. After cutting to pieces all that fell in their way, the Puritan humbugs set to at psalm-singing with tremendous vehemence. This mixture of butchery and bigotry was one of the most disgusting characteristics of Cromwell and his ferocious followers. Charles, having fled towards the Highlands, intended leaving Scotland: but some people there asked him to stop and take a bit of dinner, with the promise of a coronation in the evening.

The réunion took place, but it was rather dull, and Charles determined to make his way towards England. Cromwell resolved to pursue him, and this active friend of religion and humanity, having met a few royalists on the road, deliberately “cut them to pieces.” On the 3rd of September, 1651, the Battle of Worcester was fought, with success to the republican force; and poor Charles was obliged to escape as well as he could by assuming a variety of disguises, though how he got the extensive wardrobe his dramatic assumptions entailed a necessity for, is not quite obvious. He arrived at Shoreham, near Brighton, in a footman’s livery, and “the lad with the white cockade,” as the old song called him, obtained a situation in a coal barge, in which he was carried to France. The captain of the collier must have been an odd sort of person, to take a footman with him on the voyage, but perhaps the coal-heavers of that day were more refined than they are at present.

Cromwell was triumphantly received in London, and the cloven foot soon began to peep out from the high-low of the crafty republican. He accepted Hampton Court Palace as his residence, and an estate of £4000 a year was voted to him, without the purity of his intentions offering any obstacle to his receiving it.

The Parliament was now getting into disrepute, and Cromwell thought he would take advantage of its loss of popularity, to increase his own stock, whereupon the game of “diamond cut diamond” was commenced between them. The Parliament had now been sitting for some years, and people began to think there might be too much of a good thing, even in an assembly of red-hot patriots, that had hanged a king, and sent the country into a fit of melancholy, by prohibiting, by law, everything in the shape of cheerfulness.

In those days, a joke would lead the perpetrator to the gibbet, and a pun was so highly penal—as, perhaps, it ought to be—that a dull dog who had dropped one by mistake, was called upon to find heavy securities for his good behaviour. The nation was thrown into the dismals by Act of Parliament, and England became—to use a simile that would, at the time, have sent our heads smack to the block—the very centre of gravity. Cromwell, seeing that the Parliament was going down in favour every day, resolved to raise himself by giving the finishing blow to it. He sounded Whitelock, to whom he put the question, “What if a man should take upon himself to be king?” and thus Whitelock got a key to Cromwell’s intentions. The old man—Silverplate, as some call him,—did not take to the notion, and Cromwell was exceedingly cool to him ever afterwards. There was a meeting at Oliver’s lodgings, on the 20th of April, to discuss the best method of getting rid of the Parliament; and Cromwell, hearing the Commons were in the act of passing a very obnoxious bill, got up from his chair, in a very excited state, and told some soldiers to follow him. He swelled his little band with the sentinels on duty, whom he called out of their sentry boxes, as he passed, and entered the House, attended by Lambert, a file of musketeers, and a few officers. He took his seat, and listened to the debate, but when the Speaker was going to put the motion, he started up, saying to Harrison—”Now’s the time; I must—indeed I must!” when Harrison pulled him back by the skirts of his coat, saying to him, “Can’t you be quiet? Just think what you’re doing.” He then proceeded to address the assembly, but soon got dreadfully unparliamentary in his language, and rushing from his seat to the floor of the House, got very personal. He next stamped on the floor, when his musketeers entered, and, pointing to the Speaker, who was, of course, raised above the rest, he cried, “Fetch him down!” when the Speaker was seized by the robe and pulled into the midst of the assembly. Pointing to Algernon Sydney, Cromwell next cried, “Put him out!” and out he went like a farthing rushlight.

Algernon was very young, and exhibited at first a degree of boyish obstinacy, mixed with infantine insolence, which caused him to be refractory, or—to use a simile in conformity with the image of the rushlight—to flare up in the socket. He, for a moment, refused to go; which caused Harrison to tap him gently on the shoulder, and say to him, in a mild, but resolute tone, “Come, come, young gentleman; if you don’t go out quietly, we must put you out.” The child seemed doubtful whether to turn refractory or not, when it suddenly appeared to occur to him that it would be useless to resist; and, just as Harrison had his hands on the lad’s shoulders, to impart to him sufficient momentum to have sent him flying through the door, young Algernon made up his mind that he would go quietly. Cromwell stood, in fact, like a dog in the midst of so many rats; a position he had perhaps learned to assume, from his residence at the Cockpit; and he next flew at the mace, exclaiming, “Take away that bauble!” The mace was most unceremoniously hurried off, when, after a little more abuse against several of his old friends, the House was completely cleared, and there was an end to the Long Parliament.

Nothing could exceed the well-bred dogism or utter curishness of the Commons on this occasion, for not one of them offered the smallest resistance to the violence of Cromwell. When they had all sneaked out, he locked and double locked the door, put the keys in his pocket, and carried them to his lodgings. He admitted that he had not intended to have gone so far when he first entered the House, but the mean-spiritedness of the members had urged him on to the course he had adopted.

Thinking that he might as well make a day of it, he proposed to Harrison and Lambert to walk with him to Derby House, and the three stalked into the room where the Council of State was sitting. Cromwell at first pretended to listen with attention to what was going on, and gave an occasional loud ejaculation of “Hear!” but Bradshaw, who was presiding, soon felt that the cheer was ironical. Business was permitted to proceed in this way for a few minutes, when the Council felt it was being “quizzed,” and Bradshaw, giving an incredulous look at Cromwell, the latter made no longer a secret of his intention. “Come, come,” he cried, “there’s been enough of this; go home, and get to bed, and don’t come here again until you’ve a message from me that you’re wanted.” The hint was immediately taken by Bradshaw, who started up and ran for it—for he was afraid of rough treatment—and he presently had close at his heels the whole of his colleagues. Thus, within the space of a few hours, Cromwell had broken up the Council of State, and dissolved the Long Parliament.

Cromwell, having made short work of the Long Parliament, proceeded to supply its place by a legislature of his own composition, and the enemy of absolute monarchy proved himself an absolute humbug by acts of the most arbitrary and designing character. His pretended patriotism had in fact been a struggle on his part to decide whether the business of despotism should remain in the hands that were “native and to the manner born” to it, or whether he should start on his own account as a monopolist of tyranny to be practised for his own aggrandisement. The new Parliament was a miscellaneous collection of impostors and scamps, with a slight mixture of honest men, but these were too few to make the thing respectable. Cromwell now began to put on the external semblance of religion, with an extravagance of display that gives us every reason to doubt his sincerity. As the man of straw frequently covers himself with jewellery, a good deal of which may be sham; so Cromwell enveloped himself in all the externals of sanctity, which we firmly believe penetrated no further than the surface.

One of the principal members of the new Parliament was a fellow named Barbone or Barebone, a leather-seller and currier, who attempted to curry favour by an affectation of extreme holiness. The legislative assembly subsequently got the name of the Barebones Parliament from the person we have named, and the whole pack of humbugs usurped the powers of the State by pretending they “had a call” to take upon them the duties of government.

It may generally be observed that they who make piety a profession look very sharply out for professional profits, and if they are desirous of taking what is not justly their own, they soon get up an imaginary “call” to urge them to the robbery. Cromwell formally handed over to them the supreme authority—which, by-the-by, was not his to give—and the first day of their meeting was devoted to praying and preaching, with a view to giving the public an idea of their excessive sanctity. They soon set to work in their career of mischief, and began by abolishing the Court of Chancery, on account of its delays, which was like killing a horse because it did not happen to go at full gallop. They certainly expedited the suits, and brought them to a conclusion about as effectually as one would accelerate a steam-engine by shutting up the safety valve, and allowing it to go to smash with the utmost possible rapidity. They nominated as judges a new set of lawyers, whose qualification was that they were not in the law; and there is no doubt the Parliament would have dissolved every institution in the kingdom if the members had not dissolved themselves on the 12th of December, 1654, at the suggestion of Cromwell.

The old constitutional principle, that “too many cooks spoil the broth,” having been rapidly exemplified, it was declared expedient to have “a commonwealth in a single person,” or, in other words, to have a king with a democratic name, which is the invariable result of the policy of red-hot republicans. Cromwell was, of course, the unit who had put himself down as A1 for the new office, and he succeeded in choosing himself or getting himself chosen by the title of Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland. Thus, though the people had cut off the head of a real king, another head grew in in its place, for Government is like the hydra, which must have a head, however often the process of decapitation may be carried into execution. The brewer had, in fact, mashed up the constitution as completely as if he had used one of his own mash-tubs for the purpose, and his upstart insolence reached such a point, that the now well-known expression, “He doesn’t think small beer of himself,” was first applied in reference to this dealer in ale and stout, who, it was clumsily observed, had “gone the entire” in his great audacity.

While these things were going on at home, the English fleet had been engaged with Von Tromp, or Trump, abroad, and the Dutch sailor behaved like the article which his name delicately indicates. The Dutch for some time, though they only had this Von Trump, carried off all the honours, and sometimes succeeded even by tricks; but at length the distinguished Trump was obliged to “shuffle off the mortal coil,” and though he would gladly have revoked his determination to “cut in” to such a desperate game as an engagement with the English, he played it out to the last with all his wonted courage. The only remaining Trump, looking whistfully round him, fell by a blow from a knave who was in the suit and service of the English. When the last breath was blown out of the highly respectable Trump, the war between the Dutch and the English was at an end, and the Protector had time to follow out his principles by protecting himself with the utmost vigilance. One of his chief difficulties arose from the eagerness of the various liberal sects in religion to oppress each other in the name of brotherly love and universal harmony. This difficulty in quieting the demands of each to exterminate the others taught him lessons of diplomacy, and Cromwell soon became the most accomplished “do” that ever had a place in the pages of history. Though he recommended great tolerance in their quarrels with each other, they no sooner began to abuse him than he threw some of them into prison, reminding us of the celebrated apostle of temperance who, in a fit of intoxication, broke the windows of a public-house for the purpose of assisting the triumph of the “grand principle.”

Cromwell, who was a clever man, and, though a brewer, was averse to doing things by half-and-half, made some legal appointments that gave general satisfaction. He promoted Hale—with whom he was hale fellow well met—to the Bench of the Common Pleas, and he was fortunate enough to obtain a recognition of his protectorate from the Governments of France, Spain and Portugal.

On the 3rd of September, 1654, which was Sunday, Cromwell, as Protector, first met his new Parliament, and played the part of a king in all its most essential points, even down to the delivery of a speech from the throne, remarkable for the badness of its grammar, the antiquity of its language, and the utter emptiness of most of its sentences. He abused the levellers, for, with the skill of political engineering, he desired to level down no lower than the “dumpy level” at which he had arrived; and while eulogising liberty of conscience, he admitted it to be a capital thing so long as it did not extend to the formation of opinions unfavourable to the Protector’s own position. He spoke glowingly of the beauty of free thoughts, but hinted that, lest these thoughts should be more free than welcome, the people had better keep their thoughts to themselves as much as possible.

At the close of Cromwell’s speech, the Commons sneaked back to their House, where they elected Lenthall their Speaker, and appointed the 13th of September a day of humiliation, as if there had not been humiliation enough for the country in the conduct it had been recently pursuing. The Protector soon began to put his despotic principles in force, for his position having been debated rather freely, he sent for the members of Parliament to the Painted Chamber, and told them very plainly that he had made up his mind to stand no impertinence. “You wanted a republic,” said he, “and you have got it; so you had better be satisfied.” In vain did they venture to urge that liberty, equality, and all the rest of it had been the purpose they had in view, for he replied that “they were all equally bound to show subservience to him, and that as to liberty, they were at perfect liberty to do, say, or think anything that would not be offensive to him, their master.” He followed up this announcement by placing a guard at the door of the Parliament, whose duty it was to exclaim to each member “You can’t go in, sir, until you have signed this paper,” and on its being produced, it turned out to be an agreement not to question in any manner Cromwell’s authority. Though this was a piece of tyranny and impertinence more disgusting than anything that had been attempted by Charles, one hundred and thirty of the members yielded to it at once; for it is a curious fact that, though the people will often show the susceptibility of the blood-horse at the slightest check of the rein when it is held by a royal hand, they will manifest the stolid patience of the ass under the most violent treatment from one of themselves, who has risen to the position of their master.

On the 14th of September Cromwell’s door-keepers played their part so well, and barred the entrance so effectually against all but those who would sign the paper, that a great many more agreed to do so, and when the number of consenting parties was sufficiently respectable to make up a fair average House, Cromwell’s creatures proceeded to vote that subscribing the recognition of the Protector should be a necessary preliminary to taking a seat in Parliament.

The Protector having done everything he could for himself, proceeded to show his protecting influence—of course—over several of his relatives. Fleetwood, who had married his daughter—the widow of Ireton—was sent as governor to Ireland, and the Protector’s own son afterwards succeeded to this high and lucrative office. Not only did he provide snugly for his living kindred, but he gave them most inappropriate honours when dead, and his mother happening to go off about this time, he actually insisted on the “old woman’s” being entombed in the Abbey of Westminster. What the dowager Mrs. Cromwell had done to deserve this distinction, we have yet to learn, and as we have learnt everything connected with the subject on which we write, our instruction on this point will, we fear, be postponed to a very distant period.

Among the incidents of the Protector’s domestic life, there is one which we will insert on account of its amusing and perhaps instructive character. Cromwell’s vanity had so increased with his success, that he one day said to himself, “I can drive a whole people; I can drive a bargain as well as any man; and, odds, bobs, and buttercups! why should I not be able to drive my own carriage?” The cattle having been put to, he mounted the box with a jaunty air to enjoy a jaunt, and was tooling the cattle down Tooley Street, when, in consequence of the friskiness of one of the nags, Cromwell began nagging at his mouth with much violence. The horses not being so easily guided and controlled as the Parliament, soon turned restive, and ran away; which threw the Protector from his seat, and his own poll came into collision with the pole of his carriage. To add to the unpleasantness of the situation, a loaded pistol, which Cromwell always carried about him, went off, in sympathy, no doubt, with the steeds; or, perhaps, the charge could no longer contain itself, and exploded with a burst of indignation at the pride of its owner, who, however, was not wounded by the accident.

The Protector continued to feather his nest with unabated zeal, and he got the Parliament to vote him half a dozen different abodes, including three or four in London itself; so that, unless he took breakfast at one, at a second, and took “his tea” at a third, he could not have occupied the metropolitan residences set apart for him. Multiplicity of lodgings appears to have been a faiblesse of the Protector: for, notwithstanding these six places of sojourn, there is scarcely a suburb that has not a house or apartments to let that, according to a landlord’s myth, once served for the palace or residence of Cromwell. If we may trust to tradition, he once lived at a surgeon’s in the Broadway, Hammersmith; once in a lane at Brompton; once in Little Upper James Street, North; and once in or near Piebald Row on the confines of Pimlico. Having got an allotment of plenty of houses, to an extent reminding us of the extravagant order of “some more gigs” which an anonymous spendthrift once commanded of his coachmaker, Cromwell began to think about getting a grant to pay the expenses of his numerous establishments.[1] An allowance of £200,000 a year was settled on himself and his successors, which, we find from a document of the period, was exactly one entire sixth of the whole aggregate revenue of the three kingdoms put together.

Thus, though poor Charles had experienced the utmost difficulty in getting money granted for the payment of his debts, or even for the costs of his living like a king and a gentleman, the usurper Cromwell obtained at once the concession of a most liberal salary.

Notwithstanding the subservience the Parliament had in the first instance shown, symptoms of refractoriness in that quarter soon became visible. The Protector had made up his mind to go on changing it, as he would have done a set of domestic servants, until he could thoroughly suit himself; and accordingly, on the 22nd of January, 1656, he rang the bell, desired the legislature to appear before him, and announced that he had no further use for it. The members were desired to find themselves situations elsewhere; and though some of them had courage enough to hint that they “would be sure to better themselves, for they were tired of the quantity of dirty work they had had to do,” the Parliament evinced, on the whole, a spirit, or rather a want of spirit, that was quite contemptible. Some of the malcontents ventured on a little revolutionary rising; but the levellers were speedily reduced to their old level. Major Wildman, a man rendered wild at the success of Cromwell’s ambition, and hating the protectorate, had been heard to declare that he would “take the linch-pin out of the common-weal,” and notwithstanding the flaw in the orthography, he was imprisoned on this evidence of hostility to the ruling power. At the moment when Wildman was arrested, he was sitting alone in his own back-parlour, evincing the same sort of enthusiasm that has immortalised the three tailors of Tooley Street, and drawing up “a declaration of the free and well-affected people of England now in arms against the tyrant Oliver Cromwell, Esquire.” The major thought he had accomplished something very stinging, in adding “Esquire” to Cromwell’s name; and he was in the act of roaring out, “Hear, hear! Bravo, bravo!” after he had written out the title of his tremendous manifesto, when a sudden bursting open of the door, and a cry of “You must come along with us,” threw the major into a state of surprise from which he had not recovered when he found himself put for safe keeping in the keep of Chepstowe Castle.

A few other insurrectionary movements were made, but all of them were of a very trifling character. Penruddock, Grove, and Lucas got up a little royalist trio, but their movement was soon turned into a dis-concerted piece, by a regiment of Cromwell’s horse, who rode rough-shod over the three conspirators, and they were executed instead of their project.

The Protector was no less imperious towards foreign nations than towards his own, and having made some demands upon Spain, to which that country refused to accede, he sent Admiral Penn, familiarly termed his Nibs, to write his name upon some of the Spanish possessions. Assisted by General Venables, Penn, who may be distinguished as a steel-pen, for he carried a pointed sword, and never showed a white feather, took the island of Jamaica after a contest, in which he found among the inhabitants of Jamaica some rum customers. Blake worried the Spaniards in another quarter, and the Protector spread so much consternation among some of the European governments, that the celebrated Cardinal Mazarin, who greatly feared him, began to look so very blue, that a Mazarine blue retains to this very day a character for intensity.

Emboldened by his good fortune, Cromwell thought he might venture on another Parliament, which met on the 17th of September, 1656, the members having undergone at the door an examination as to their servility to the Protector’s purposes. The first sitting was like the first night of any novelty at the pit of Her Majesty’s Theatre, and two of Cromwell’s creatures officiated as check-takers. Every member who presented himself at the doors was obliged to produce his credentials, and upon this being satisfactorily done, a cry of “Pass one,” was raised to the officer in charge of the inner barrier. Nearly one hundred new members were sent back, after more or less altercation; and the words “I can’t help it, sir; those are my orders; you must go back, sir,” were being continually heard above the din of “Pass one,” or “It’s all right,” which confirmed the privilege of admission claimed by many of the applicants.

A legislature with only one House soon began to be considered as a sort of sow with one ear, and even the ear that remained was closed by Cromwell’s art against what he used to call in private “the swinish multitude.” A suggestion was made by several that the House of Lords should be restored, and many began to sigh for a return to the old constitution, which had been broken up before there had been time to try the effect of a new one.

At length an alderman of London, one Sir Christopher Pack, started up, without any preliminary notice, and moved that the title of king should be offered to the Protector. Pack’s proposition set off the entire pack of republicans in full cry against him, and they all continued to give tongue from the 23rd of February to the 26th of March, 1657, when Pack’s motion was carried by a large majority. A deputation was appointed to request that “his Highness would be pleased to magnify himself with the title of king,”—a proposition almost as absurd as an offer to place Barclay and Perkins on the throne, or entreat Meux and Co. to write Henry IX. over the door of their brewery.

Cromwell gave an evasive reply to the requisition, approving most fully of the proposition to restore the House of Lords, but was hanging back about the “other little matter,” when a declaration from some of his former friends and tools, that they had fought against monarchy and would do so again if required, completely settled him in his wavering refusal of the royal title. He was therefore inaugurated with much pomp as Lord Protector—and, indeed, he might well have been satisfied, for he had secured everything except the name of royalty. His manner of life and his Court were marked by no extravagant show, but he had everything very comfortable: and he was accustomed to say to his intimate friends, “What do I want with the gilt, for haven’t I got the gingerbread?” He did not give very large parties at Hampton Court, but used to have a “few friends” to tea, and “a little music” in the evening.

He occasionally attempted a joke, “But this,” says Whitelock, “was always a very ponderous business.” One of his frolics—we start instinctively at the idea of Cromwell being frolicsome—was to order a drum to beat in the middle of dinner, falling unpleasantly on the drums of his guests’ ears, and at the signal the Protector’s guards were allowed to rush into the room, clear the table, pocket the poultry, and, on a certain signal from the drum, make off with the drumsticks.

Cromwell had the good taste to delight in the society of clever men, and there was always a knife and fork at Hampton Court for Milton, or for that marvel of his age, the celebrated Andrew Marvel. Waller, the poet, was welcome always; Dryden now and then; John Biddle sometimes; and Archbishop Usher, whom Cromwell use to call the only real gentleman usher of his day, was constantly kicking his heels under the Protector’s mahogany.

We have now to record the death of poor Blake, who, having fluttered the Canaries in the isles of that name, was returning safe into Plymouth Sound, when he died of the scurvy, which, according to a wag of that day—happily the wretch is not a wag of this—showed that fortune had in store for him but scurvy treatment. Poor Blake had been in early life a candidate for an Oxford fellowship, but lost it from the lowness of his stature,[2] for in Blake’s time very little fellows were not academically recognised. There is no doubt that with his general ability he would have taken a very high degree if he had been only big enough. He was buried at the Protector’s expense, in Henry the Seventh’s chapel, for Cromwell was a great undertaker, and was very fond of providing his friends with splendid funerals.

While these things were happening at home, the Protector was fortifying his position abroad, and had persuaded the French to abandon Charles the Second, known to the world in general, and to playgoers in particular, as the “merry monarch.” This fugitive scamp—of whom more hereafter—was mean enough to offer to marry one of the Misses Cromwell, a daughter of the usurper, who had the good sense and spirit to turn up his puritanical nose at the idea of such a son-in-law. Orrery, whom Charles consulted with the vague idea that consulting an orrery was in fact consulting the stars, took the message to Cromwell, who replied, haughtily, “I am more than a match for Charles, but Charles is less than a match for my daughter.” The Protector had what he called something better in view for his “gal,” who, on the 17th of November, was wedded to Lord Falconbridge. The ceremony was described in the Morning Post of the period, which was then called the Court Gazette, and a column was devoted to an account of the festivities. We see from facts like these how ready are the declaimers against aristocracy to adopt the ways and even the weaknesses of a class that is ridiculed and abused chiefly by those who would, if they could, belong to it.

The ascendency of the puritan Protector was marked by the grossest corruption that ever prevailed under the most licentious of regal governments. Unlimited bribery of one portion of the people was effected by the unlimited robbery of the other, and thus the dupes were made to pay the knaves who sold themselves and betrayed their fellow-subjects for the sake of Cromwell’s aggrandisement.

On the 20th of January, 1658, the Parliament met again, and fraternised with a little batch of peers, amounting to sixty in all, whom Cromwell had created, and who might, indeed—upon our honour, we don’t say so for the sake of the pun—be justly called his creatures. Two of the Protector’s sons, namely, Richard and Henry, were among the batch of anything but thoroughbreds, that formed the roll of Oliver’s peerage. The number, however, included some highly respectable names, among whom we may particularly notice Lord Mulgrave, who took the family name of Phipps, because in the civil wars he would not at one time have given Phippence for his life; Lord John Claypole, whose head was as thick and whose brains were as muddy as his title implies; and a few old military friends of Cromwell. Colonel Pride, who had been a drayman, was also among the new peers; and the drayman of course offered a fair butt to the royalists, who threw his dray in his face and assailed him with the shafts of ridicule.

Scarcely any of the genuine nobles who had been called to Parliament condescended to come, and the Protector made his appearance before a house almost as poor as some of those in which the farce of legislation is enacted in these days at nearly the close of a very long session. Cromwell was really indisposed, or shammed indisposition on account of the scantiness of the audience, for, after having said a few words, he turned to his Lord Speaker Fiennes, exclaiming, “Fiennes! you know my mind pretty well; so just give it them as strongly as you like, for I’m too tired to talk to them.” Fiennes, taking the hint, proceeded to rattle on at very rapid rate, mixing up a quantity of religious quotations and a vast deal of vulgar abuse, in the prevailing style of the period.

The Commons retired to their chamber in a huff; and four days afterwards, receiving a message mentioning the Upper House, refused to recognise the peers except as the “other house,”—for the little Shakspearean fable of the rose, the odour, and the name, was not at that time popular. The Protector, who always sent for the Parliament as he would have sent for his tailor, desired that the legislature should be shown into the banqueting or dining-room, where he advised them not to quarrel, and, producing the public accounts, he impressed upon them that things were very bad in the city. He exhorted them not to increase the panic by any dissensions among themselves, but he could not persuade them to change their note; and he accordingly got out of bed—some say, wrong leg first—very early on the 4th of February, when, calling for his hot water and his Parliament, he dissolved the latter without a moment’s warning. The legislative body had enjoyed a short but not very merry life of fourteen days, when an end was thus put to its too weak existence.

The Protector was now in need of all his protective powers in consequence of the dangers that on all sides threatened him. The republicans were ready, as they generally are, to draw anything, from a sword to a bill; and the army, with its pay in arrear, did nothing but grumble. The royalists were being inspirited by the Marquis of Ormond, who was “up in town,” quite incog.; and the levellers were, of course, ready to sink to any level, however degraded, in the cause of the first leader who was willing and able to purchase them.

Notwithstanding the gathering storm, Cromwell boldly stuck up the sword of vengeance by his side, as a sort of lightning conductor to turn aside the destruction that threatened him. A pamphlet, called “Killing no Murder,” put him to the expense of a steel shirt, the collar of which, by the way, could have required no starch; and he kept himself continually “armed in proof,” but we do not know whether he selected an author’s proof, which might have been truly impregnable armour, for getting through an author’s proof is frequently quite impossible. He carried pistols in his pockets, to be let off when occasion required—a provision of which he never gave his enemies the benefit. Poor Dr. Hunt was cruelly cut off—or, at least, his head was—which amounted to much the same thing; and others were treated with similar severity.

On the Continent the Protector was very successful, and the English serving under Turenne, or, as some have called him, Tureen, poured down upon Dunkirk, which was overwhelmed and taken. Cromwell, however, lived a miserable life at home, being suspicious of every one about him, and he never dared sleep more than two consecutive nights in the same place—a circumstance that may account for the multiplicity of lodgings we have already alluded to. This continual changing of apartments must have rendered him very liable to get put into damp sheets, and, as hydropathy had not yet been reduced to a system, he caught the ague, instead of profiting by the moisture of the bed-clothes. On the 2nd of September he grew very bad indeed, and, in the presence of four or five of the Council, he named his son Richard to succeed him; but this youth was so complete a failure, that to talk of his succeeding was utterly ridiculous. Oliver Cromwell died between three and four o’clock in the afternoon of the 3rd of September, the day on which he always expected good luck, for it was the anniversary of some of his greatest victories. Death, however, is an enemy not to be overcome, and, in spite of the prestige of success which belonged to the day, the Protector was compelled to yield to the universal conqueror. He died in the fifty-ninth year of his age; and it is a singular coincidence that Nature brewed a tremendous storm—as if in compliment to the brewer—at the very moment of his dissolution.

The character of Cromwell was, as we have already intimated, a species of half-and-half, in which the smaller description One, Two, Three, and finder of beer appeared to preponderate. He had, like a pot of porter, a good head; but to draw a simile from the same refreshing fount, he was rather frothy than substantial in his political qualities. His speeches had the wonderful peculiarity of meaning nothing, and instead of saying a great deal in a few words, he managed to say very little in a great many.[3] Cromwell wrote almost as obscurely as he spoke, and could do little more than sign his name, for which he used to make the old excuse of the illiterate, that his education had been somewhat neglected; and indeed it seemed to have gone very little beyond those primitive pothooks intended for the hanging up of future more important acquisitions. The Protector’s wit was exceedingly coarse, or rather particularly fine, for it was scarcely perceptible. It savoured much of the Scotch humourist, whose fun might be exceedingly good sometimes, if it were not always invisible. His practical jokes wore not particularly happy, and his smearing the chairs with sweetmeats at Whitehall, to dirty the dresses of the ladies, was a piece of facetiousness worthy of an eccentric scavenger, but highly unbecoming to the chief magistrate, for the time being, of such a country as England.

Though Cromwell could scarcely read the characters of caligraphy, he could peruse the characters of men with great acuteness. He was well acquainted with all the variations of human types, and could easily distinguish the capitals from the lower-case. In private life he was playful, though in his public capacity he was severe even to cruelty; and it has hence been prettily remarked, that, though he was a kitten in the bosom of his family, the puss became a tiger in the arena of politics. He never turned his back upon any of his children, except at leap-frog, in which he would often indulge with his sons, who had little of that vaulting ambition for which their parent was conspicuous.

[1] Statement of a sub-committee of the Commons.

[2] Brodic, Brit. Emp., iv. 317.

[3] The following is an extract from one of the Protector’s speeches, which even Captain Bunsby, the naval oracle in “Dombey and Son,” might be proud of: “I confess. I would say, I hope, I may be understood in this, for indeed I must be tender in what I say to such an audience as this;—I say, I would be understood that in this argument I do not make a parallel between men of a different mind.”—Original Speech of Oliver Cromwell.

Very good, very good, excellent background for Reynolds. Basic you might say. Is there a way to shift your WordPress posts over to my site easily?